AP May 17, 2023–Thousands of Americans each year turn to state-run programs that provide financial assistance to victims of violent crime. The money is used to help with funeral expenses, physical and emotional therapy, lost wages, crime scene cleanup, and more.

While interviewing people for a story on gun violence in Philadelphia, The Associated Press heard from the victim after victim that they had received a form letter denying them access to the funds. In many cases, the state said they or their loved one had contributed to their own victimization.

The AP sought to find out from the Pennsylvania program — and then programs in all 50 states and the District of Columbia — who was being denied aid and why. This week’s article is the third in an occasional Associated Press series examining crime victim compensation programs.

To read parts one and two, https://apnews.com/arti- cle/victims-compensation-crime-racial-disparity- 00ff7bfa3f3263c3e2fef025450b8411

A look at the takeaways from the AP’s investigation.

**********

AP July 25, 2023–Pamela White stared at the silver tree with twinkling lights while she cleaned out her son’s apartment, wondering how in a matter of days she went from celebrating Christmas to having to think about headstones and burial plots.

Her son, Dararius Evans, was an Army reservist and veteran who had survived a deployment in Iraq. A few days after Christmas 2019, the 28-year-old was killed in a shooting outside of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The shooter was sentenced to life in prison last year.

White and her family, who live outside of New Orleans, turned to Louisiana’s victim compensation board for help paying for the unexpected funeral. She was met with administrative hurdles, a denial that blamed her son for his own death, and a lengthy appeal — all while paying up front through a personal loan that gathered interest as she waited.

Thousands of crime victims each year are confronted with the difficult financial reality of state compensation programs that are billed as safety nets to offset costs like funerals, medical care, relocation, and other needs. Many programs require victims to pay for those expenses first and exhaust all means of payment before they reimburse costs, often at rates that don’t fully cover expenses.

The programs also struggle under often unstable fund- ing mechanisms that leave their budgets vulnerable to shortages and the changing priorities of lawmakers. Well-intentioned prison and criminal justice reforms aimed at reducing incarceration have caused shortfalls in some states that rely heavily on court or prison fines and fees for funding.

Advocates say most states’ requirement that victims pay upfront can leave out people living on the edge of financial disaster who are often most vulnerable to a crime.

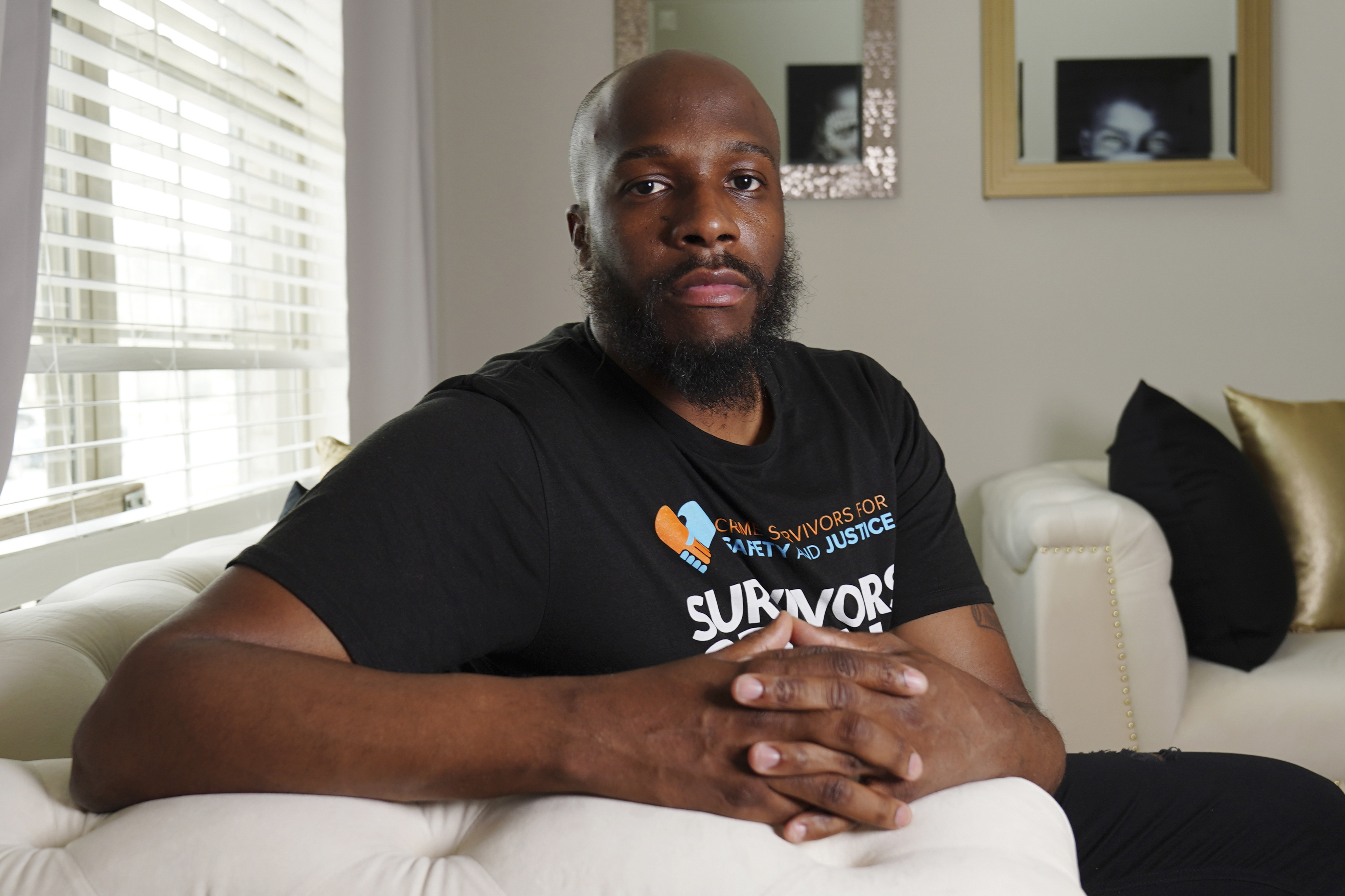

“So many families often can’t rely solely on that reimbursement model. …Those funds take months to arrive to families,” said Aswad Thomas, vice president of the Alliance for Safety and Justice, a nonprofit working to reform victim compensation and other aspects of the criminal justice system.

Some programs do offer to directly pay funeral homes or medical providers. But for victims in places that don’t, the expense can mean not being able to pay rent or having to decline services like counseling because the grocery bill is more pressing.

Programs also require victims to exhaust other payment options first, like insurance, lawsuit awards or even crowdfunding. If a family member or friend starts a GoFundMe drive, it could cause some programs to reduce an award or claw back already granted money.

The wait for help also causes financial strain. While some states report claims are processed within days, others take months ,…

Thank you for reading Mike Catalini and Claudia Lauer article on scoopnewsusa.com. For more on “Safety net with holes? Programs to help crime victims can leave them fronting bills“, please subscribe to SCOOP USA Media. Print subscriptions are $75 and online subscriptions (Print, Digital, and VIZION) are $90. (52 weeks / 1 year).