Like most children, I dreamed of being many things when I was growing up. I wanted to be a schoolteacher. I wanted to be a dancer, an actress, a doctor, a police officer, a fireman and yes, I wanted to be a nurse. I had many examples around me, growing up, of African American women who were nurses and I just thought that would be the coolest profession to be in.

At the age of 14, I signed up for the candy striper program at Einstein Medical Center and it was there that I figured out I didn’t have what it took to be a good nurse. The sight of blood makes me dizzy. The sight of needles, or the thought of giving a needle to someone else, makes me want to cry. Then the idea of having to clean someone up who is a grown person, and doesn’t have control of their bowels, nope, not for me. Nonetheless, I am thankful for the experience I received at such a young age. I wish hospitals still offered those kinds of programs for youth today.

I share a slice of my personal story about my short-lived dream of becoming a nurse because I have such great respect for people in that profession.

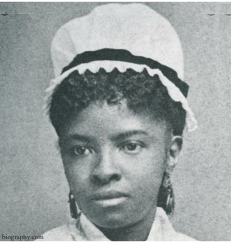

As we continue to observe Black History Month, in my column today, I am shining the spotlight on a woman, who may not be well known, but who after today, I hope, will be remembered by those who read this SCOOP column.

The information I am sharing about Mary Eliza Mahoney, I got online from Wikipedia.

Mary Eliza Mahoney was born on May 7, 1845, and she died on January 4, 1926. Her claim to fame is that she was the first African American to study and work as a professionally trained nurse in the United States. In 1879, Mahoney was the first African American to graduate from an American school of nursing.

Mahoney’s parents were freed slaves, originally from North Carolina, who moved north before the American Civil War in pursuit of a life with less racial discrimination. She was the oldest of two children. Mahoney was admitted into the Phillips School at age 10, one of the first integrated schools in Boston, and stayed from first to fourth grade. Phillips School was known for teaching its students the value of morality and humanity, alongside general subjects such as English, History, Arithmetic, and more. It is said this instruction influenced Mahoney’s early interest in nursing.

Mahoney knew early on that she wanted to become a nurse; possibly due to seeing the immediate emergence of nurses during the American Civil War. Black women in the 19th century often had a difficult time becoming trained and licensed nurses. Nursing schools in the South rejected applications from African American women, whereas in the North, though the opportunity was still severely limited, African Americans had a greater chance at acceptance into training and graduate programs.

At the age of 18, as soon as the New England Hospital for Women and Children was created, she began to show an interest in nursing. The NEHWC became the first institution to offer a program allowing women to work towards entering the healthcare industry, which was predominantly led by men.

She was admitted into a 16-month program at the New England Hospital for Women and Children (now the Dimock Community Health Center) at the age of 33, alongside 39 other students, in 1878. Her sister, Ellen Mahoney, also decided to attend the same nursing program but was unsuccessful in receiving her diploma.

The criteria which the hospital utilized while choosing students for their program emphasized that the 40 applicants would be “well and strong, between the ages of 21 and 31, and have a good reputation as to character and disposition.” Out of a class of 40 students, she and two other white women were the only ones to receive their degrees. It is presumed that the administration accepted Mahoney, despite not meeting the age criteria, because of her connection to the hospital through prior work as a cook, maid, and washerwoman there when she was 18 years old. Mahoney worked nearly 16 hours daily for the 15 years that she worked as a laborer.

Mahoney’s training required she spend at least one year in the hospital’s various wards to gain universal nursing knowledge. After completing all requirements, Mahoney graduated in 1879 as a registered nurse alongside 3 other colleagues – the first Black woman to do so in the United States.

After receiving her nursing diploma, Mahoney worked for many years as a private care nurse, earning a distinguished reputation. She worked for predominantly white, wealthy families. The majority of her work was done in New Jersey with new mothers and newborns, with the occasional travel to other states. During the early years of her employment, African American nurses were often treated as if they were household servants rather than professionals. Mahoney emphasized her preference to eating dinner alone in the kitchen, distancing herself from eating with the existing household help, to further dismiss the difference in the relationship between the professions. Mahoney also lived alone in an apartment in Roxbury.

Families who employed Mahoney praised her efficiency in her nursing profession. As Mahoney’s reputation quickly spread, she received private-duty nursing requests from patients in states on the north and southeast coast.

From 1911 to 1912, Mahoney served as director of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum for Black children in Kings Park, Long Island, New York. The asylum served as a home for freed colored children and the colored elderly. This institution was run by African Americans. Here, Mary Eliza Mahoney finished her career, helping people and using her knowledge as best she knew.

In 1896, Mahoney became one of the original members of the then-predominantly white Nurses Associated Alumnae of the United States and Canada (NAAUSC), which later became the American Nurses Association (ANA). In the early 1900s, the NAAUSC did not welcome African-American nurses into their association. In response, Mahoney co-founded a new, more welcoming nurses association, with help of Martha Minerva Franklin and Adah B. Thoms.

In 1908, she became a co-founder of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN). This association did not discriminate against anyone and aimed to support and congratulate the accomplishments of all outstanding nurses and to eliminate racial discrimination in the nursing community. The association also strived to commemorate minority nurses on their accomplishments in the registered nursing field.

Mahoney was inducted into the American Nurses Association Hall of Fame in 1976. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1993.

All medical personnel are front-line workers, and today as we continue to live through the Coronavirus pandemic, many of us understand now more than ever, just how critical people in the medical professions are to our health.

Black nurses stand on the shoulders of Mary Eliza Mahoney

Reading Time: 4 minutes