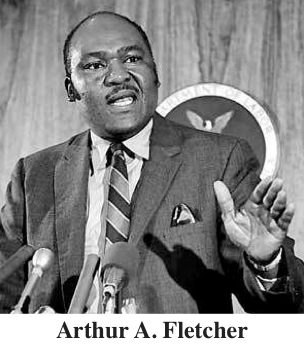

Known as the “Father of Affirmative Action” for his crafting of the Philadelphia Plan, the late, great Arthur A. Fletcher is credited with starting the affirmative action movement in the U.S.

In 2001, I was blessed to meet and interview Fletcher while participating in a meeting of the Minority & Women Business Enterprise Statewide Taskforce in Harrisburg. The taskforce, organized by then Pennsylvania Auditor General Bob Casey, Jr., had been developing strategies to address inequities in the awarding of state contracts. So, it was appropriate that Fletcher – longtime civil rights activist, battled-scarred warrior in the fight for economic justice for African Americans – advise the taskforce on strategy.

Most people don’t know that he was instrumental in the success of Brown vs. Topeka, the landmark case that called for desegregation of public schools. In addition to being one of the plaintiffs, Fletcher traveled the nation raising funds for the case led by Thurgood Marshall and his legal team at Howard University’s School of Law.

An air of excitement spread through the meeting when it was announced that Fletcher would be the keynote speaker at the next day’s luncheon. We were about to be exposed to one of the great thinkers of the nation. When the tall, stately elder rose to the podium, everyone leaned forward in anticipation of his words of wisdom. He reminded us that we were “standing on the shoulders of giants” and “ancestral freedom fighters” like Frederick Douglas, Booker T. Washington and Mary McCleod Bethune, who inspired him when she spoke at his primary school.

Fletcher revealed how his commitment to the case and backlash from the white establishment nearly cost him everything he had. He lost his job and was “blacklisted” nationwide. Employers wouldn’t touch him with a 10-ft. pole. The pressure on his family was unbearable and his wife at that time committed suicide, leaving him with five children to raise alone. This would have broken a weaker person, but he was undaunted and continued the quest for economic justice for his people.

Fletcher had a wealth of leadership experience. Early in his career, he served as director of the Washington Manpower Development Project in Pasco, Washington; employee relations specialist at Hanford Atomic Energy facility in Richmond, Washington; special assistant to the Governor of Washington; assistant secretary of labor, U.S. Department of Labor; U.S. delegate to the United Nations; vice chair of the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation, and chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. He was an advisor to Presidents Nixon, Ford, Reagan and George H.W. Bush. He was the first African American elected to Pasco City Council. He even ran for lieutenant governor of Washington State in 1968, won the primary and came very close to winning. As executive director of the United Negro College Fund, he helped coin the slogan, “A mind is a terrible thing to waste.” He was chair of the National Black Chamber of Commerce and CEO of Arthur Fletcher’s Learning Systems at the time of his transition in 2005.

Fletcher started teaching and we listened intently. He said groups like the taskforce must develop strategies and tactics like the Philadelphia Plan that used contract law, not social justice to deal with economic equity. Fletcher said information needed to develop an economic strategy is provided by the Federal Reserve, the Comptroller of Currency Fiscal Division, the Federal Credit Union, the FDIC and the Community Reinvestment Act.

“These agencies regulate the economy of this country,” he explained. “They must be put on notice that we will examine their performance on the census tracts where African Americans and other people of color live.”

He stressed the importance of using the Community Reinvestment Act to revitalize our communities. “The CRA was developed to improve the quality of life in depressed neighborhoods. It has criteria which demonstrates how you service the area, the products and services you provide and the investments you make. The CRA is targeted to our neighborhoods and the banks are committed to that plan for three years. Those of us on the state and local government level must feel the responsibility to make opportunities available so others can stand on your shoulders.”

Fletcher believed in being prepared and said Black folks must “steep themselves in the facts.” He said documents such as the Federal Reserve Community Affairs Consulting Report lists the credit worthiness of every city zip code by zip code and documents how much money is in each census tract. He noted that the Occupational Outlook Handbook lists which professions will be in demand in the future. “They can’t replace all of the workers without us, but we must be prepared,” he said.

On the question of reparations, Fletcher said it makes sense, but we should take a closer look at the CRA and use it for our benefit. “We must tell our legislators to become well-versed in the CRA. If they don’t respond, get folks from the universities who know the CRA to hold seminars and workshops in the community every 90 days until you feel comfortable representing yourselves to get our piece. Get the credit worthiness study from the Federal Reserve Board so you can understand how the government is holding the banking industry’s feet to the fire. Once we do that, we can develop strategies and tactics to get economic equity. That’s your reparations. Nobody’s going to do it for us. We’ve got to do it for ourselves.

They can debate reparations from now until whenever. I want to make sure that we take full advantage of this piece of legislation that is already on the books.” I admit we slept on his advice, but the information is still here for us to use.

He even gave us a reading list to prepare for the fight for economic justice: 1) Passionate Attachment, chapter 10 by Ball & Ball, on how the Jewish became a force in American politics; 2) Mormon America, page 155 on Mormons, Incorporated and how they use tithes to make the CRA work for them; 3) The Future While It Happens by Samuel Lubell, shows what the opposition does to Blacks in politics and 4) Preparing To Make War by James Dungan, on war strategy that can be used to plan strategy for economic warfare.

He had confidence in us and said, “Keeping the flame is an eternal struggle. What the power structure has been saying to us is, what’s your agenda, give us a plan, don’t expect us to fashion a plan for you, fashion one for yourself.” Ashe on that!

Fletcher was a highly spiritual man, full of insight. His spiritual and mental strength, his courage, his vast life experiences and far- reaching insight on how to work the system for the benefit of the people bolstered is invaluable. He was a lifelong republican. He spoke up loud and often on behalf of his people. Now days, Black people ostracize Black republicans. We are the only ethnic group that discards our people over politics. Fletcher understood what many do not — it’s your commitment to your people that really matters. Now, it’s up to each of us to continue his wonderful legacy.