The Civil War was over at last and all attention was turned to the reconstruction of its aftermath. The true and final test now was to see if this long-fought war for democracy would work for a nation bent towards peace.

Perhaps the real challenge of this democracy was embodied in the tasks of the first seven Black men elected to the U.S. Congress. For not only were they expected to help resolve the imminent post-war issues. They were also expected to assist the millions who now had been newly awarded rights and citizenships handed them through the Emancipation. These newly freed citizens expected to receive the guarantee of their “40 acres and a mule.”

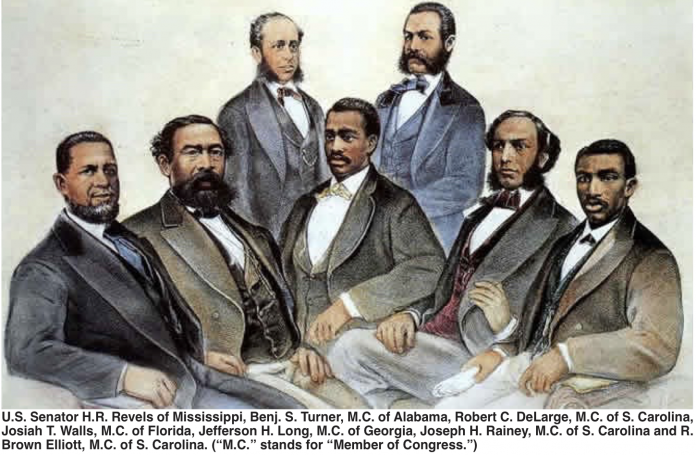

The seven, sent to face these challenges during the presidential term of Ulysses S. Grant were Hiram R. Revels, Benjamin S. Turner, Josiah T. Walls, Robert C. DeLarge, Joseph H. Rainey, Robert Brown Elliott and Jefferson Long.

All were Republicans; all were from Southern states. Three had been born into slavery and all but two were either self-educated or had little more than a year of formal education.

One was an ordained minister; one was a barber. One was a lawyer and two had been businessmen.

Thus, arriving in Washington, outnumbered and braving open hostilities, they were seated among those long familiar with all “due processes of law.”

Except for menial political jobs and activities within the Freedmen’s Bureau, all seven had been excluded from the mainstream of politics.

When Senator Revels from Mississippi was seated in the U.S. Senate for an unexpired term of a retiring Senator, Senate Democrats, showing open opposition, argued that he did not meet the citizenship requirement to occupy the seat. The issue was debated three days before being settled.

Finally, Senator Revels, though often having to relinquish the assembly floor, was able to speak out against the abuses on Blacks by the old southern aristocracy. While on the Education and Labor Committee he pleaded, though unsuccessfully, for the integration of schools.

Feeling totally defeated in his endeavors, and knowing there was little chance for re-election, Senator Revels returned home to the ministry.

Another Black was run against Representative Turner of Alabama after he served a full term in the 42nd Congress, and with the vote split, the other party seated their candidate.

Having been a delegate to the state constitutional convention, Rep. Walls of Florida was elected first to the lower house of the state legislature and then to the state senate.

He faced bitter opposition after winning Florida’s only congressional seat and was unseated a month before the term ended. He, however, won the second seat granted Florida, and served though the 43rd Congress, but when re-elected, political enemies once again disputed his election and he was unseated after serving a month. Little energy was left for Rep. Walls to concentrate on his real duties in the Congress. When he lost his next nomination, Rep. Walls served for a time in the state legislature and later returned to Florida where he became superintendent of what is now Florida A&M University.

During the conclusion of the 41st Congress Rep. Rainey of South Carolina was appointed to fill a seat made vacant when the credentials of another congressman were not accepted.

The first member of the House, he served for two terms and lost in the next election. He left Congress to work for the Internal Revenue Service. Later he entered the banking and brokerage business.

Before going into Congress, Rep. Elliott had served for three years in the state legislature. It is said that few men in the 42nd and 43rd Congress, were able to match his brilliance, for as a lawyer, he was more than able to mach wits against his opponents. Upon his resignation, he resumed his law practice in New Orleans.

Rep. DeLarge, also of South Carolina, was seated nearly a year before devious tactics were used to have him unseated, and the seat remained vacant for the remainder of the term. Rep. DeLarge returned to Charleston where he was named city magistrate.

Even after Rep. Long was elected, Congress took so long to work out the compromise under which Georgia was to be re-seated that his term had almost expired before he was seated.

He became so disheartened with his congressional experiences that he declined to run again.

Now the seven sit – fixed in time-in a 19th Century Currier & Ives lithograph that is simply titled, “The First Colored Senator and Representatives in the 42nd and 43rd Congress of the United States.”

Many lesser known Blacks achieved prominence in southern state and local governments during the aftermath of the Emancipation, some, possibly even more qualified than they were for congressional leadership. But, they met the challenges of the new American democracy with what they had.

And as James G. Blain, a statesman of the time wrote, “The colored men who took seats in both the House and the Senate did not appear ignorant or helpless. They were, as a rule, studious, earnest and ambitious men whose public conduct would be honorable to any race.”